Towards a workable regulatory environment for Europe's platform economy

More regulation for the platform economy is rapidly emerging. The goal of these new regulations is a fair platform economy for all. What impact do they have? How can we make legislation more workable for all? And how do these lessons help us prepare for new regulations around technology like AI? Independent platform expert Martijn Arets organised the 'Regulating Digital Platforms Working Conference' on behalf of The Hague University of Applied Sciences and together with PwC and Considerati. In this blog, he shares his insights.

Companies like Meta, Amazon and Just Eat Takeaway have seen more regulations imposed on them in the past few years than in the 20 years before. After years of hardly any specific regulation for platforms, Europe is catching up. Now that the first new regulations for the platform economy are in place, I decided it was time to take stock and look ahead.

Therefore, from the Platform Economy lectureship of The Hague University of Applied Sciences, I organised the 'Working Conference on Regulating Digital Platforms' together with PwC and Considerati. Attendees: everyone involved in platform regulation from the Netherlands and EU. Some 50 policymakers, regulators, researchers and entrepreneurs (both big-tech and start-ups and scale-ups) attended. The aim: to learn from each other and look ahead to what works.

New and updated regulation for a fair platform economy

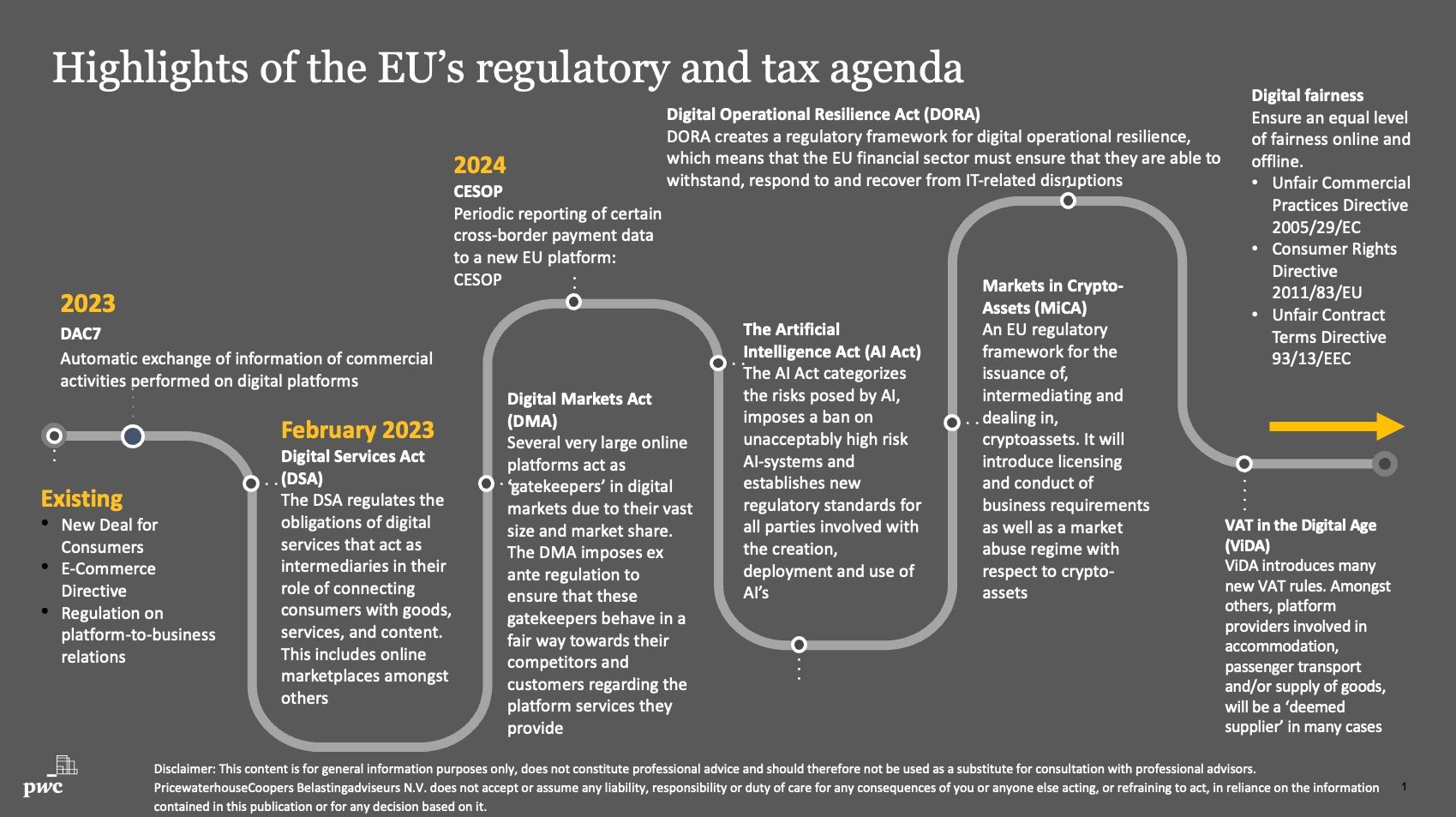

To ensure that European legislation remains up to date, the European Commission under President Von der Leyen introduced the strategy 'A Europe fit for the digital age'. Under this strategy, several laws that have entered into force or will soon enter into force in the past year have been worked on, such as the Digital Services Act (DSA), Digital Markets Act (DMA), the DAC7 and VAT in the Digital Age (ViDA).

The aim of all the new regulations is a fair platform economy for all. Many new regulations therefore deal with issues such as market power, equal access, protection of users' fundamental rights and fair competition between providers and platforms. Indeed, by nature, the platform economy is a market in which the biggest players compete away from smaller companies relatively quickly. In any case, the biggest players often set the rules. There is self-regulation in the sector, but platform entrepreneurs and policymakers agree that this is not enough. They believe a democratic countervailing power is needed. And so do I.

It is important to evaluate the establishment, implementation and enforcement of new regulations because technology such as Artificial Intelligence (AI) will play an increasingly decisive role. The European Commission is working on more and more legislation around this, think of the 'AI act'. The insights from recent changes are essential to make those new regulations workable and effective.

Speed, hammers and ambiguities

During the working conference, policymakers and entrepreneurs agreed that the rapid introduction and short implementation times of new legislation is causing problems. They welcome the government's decisiveness, but sometimes the pace leads to so-called 'hammers': measures that are too generic to apply to all the different manifestations of platforms.

Indeed, industry-wide legislation is often based on court rulings on a specific type of platform. As a result, it is sometimes not entirely clear how such a law affects a platform with a different technology or business model. For example, the DSA is clear for marketplaces on which people trade products, but not for marketplaces for services.

That there are many new regulations coming quickly is also a practical challenge. Platforms suddenly have to switch gears in very many fields: adjustments in work processes, ICT, compliance, governance and in their relationships with regulators or partners, for example. Entrepreneurs struggle to decide which new obligations they should and can implement first. Shortages of technical staff are also seen as a complicating factor. Small SME organisations in particular find it difficult to set priorities.

In addition, the question should always be asked first whether new legislation is the means to an end and whether certain obligations are not already included in existing non-platform specific regulations. After all, new legislation is not an end in itself, but one of the means to an end.

Give SME platforms a voice too

More than 95% of platform organisations are SMEs, while (very) large platforms dominate public perception, lobbying and debate. It is important to also involve and give a voice to small and medium-sized players at an early stage, as laws and regulations often have different impacts for them.

For instance, it became clear that SMEs need more help in implementing new laws. SME platforms want to participate, but often simply do not know how to do it. There is often a lot of room for interpretation, so they choose the simplest route. But that is not always the right one. Online seminars, toolkits and API interfaces can make things easier for these entrepreneurs. Policymakers are aware of the differences between large and small entrepreneurs and are keen to address them.

Improve communication and cooperation

There is also a lack of cooperation and communication when introducing new legislation. For instance, different government departments do not always know from each other what measures they are working on. This sometimes also applies to (large) platform companies, which are often organised in multiple product categories, which are subject to legislation. How should they implement those regulations in existing data structures? This requires cooperation: in the chain and between lawyers and engineers. This is often lacking now.

For instance, data collection and reporting requirements are essential in the new tax directives. Both platform companies and regulators struggle with their interpretation. A lot of data is available, but how do you process it? To what extent is it actually allowed under privacy laws (think reporting social security numbers)?

Connect policy and implementation

The biggest problem is that policy and implementation are often two different worlds. One example: the Senate (Eerste Kamer) of the Dutch Parliament (the States General)did not make a final decision on the DAC7 Act until 20 December 2022, while companies had to have implemented it by 1 January 2023. Also, when the Platform-to-business regulation was introduced, many platforms did not know exactly where they stood, due to the lack of concrete guidance such as guidelines.\

To improve this, two things need to happen. First, it would be better to put individuals and businesses to whom the law applies at the centre, rather than silos in the drafting process. Second, better connection is needed between the different design, introduction and implementation phases. Lastly, uniformity in the national translation of legislation between member states is very important. This will prevent European legislation from being applied differently in each country - including by supervisory authorities.

Importance of association

Furthermore, individuals and companies affected by new legislation are often involved too late. If the government asks for their input at all, it is often at the final stage. This is unfortunate, not only because it delays implementation. Many platforms have been working on the issues for a long time, in their own way. Dealing decently with users, explaining processes and balancing business and customer interests make sense to many entrepreneurs. So they can certainly contribute ideas on the right measures.

An additional difficulty is that bodies such as the Tax Administration do not always have the capacity to engage in discussions with individual companies, and therefore work through, for example, trade associations. This is problematic, as such associations hardly exist in the Dutch platform economy. It would be good to speed up association, and perhaps the government can help. For instance, the UK government demanded the platform sector to unite, with success: this led to Sharing Economy UK. In the Netherlands, partly thanks to encouragement from the Ministry of Finance, an association has been set up around crowdfunding. Uniting also contributes to better implementation: for instance, the Tax Authority actively seeks to connect with entrepreneurs to help them implement.

Conclusion

The high attendance at the Working Conference makes it clear that there is interest from all sides to talk and learn about this topic. In doing so, the discussion was very lively, open and substantive. Of course, each party has its own interests, but it is clear that there are also many common needs. Both platforms and public organisations see the importance of values such as safety, competition, a fair platform economy - and of course entrepreneurship! And both policymakers and entrepreneurs are struggling with the introduction of lots of new laws at the same time.

Dialogue remains essential. Break through silos to better determine the joint effect of regulations. A central coordinator to determine urgencies could be a solution. Such a person or body has an overview and can thus determine when it is time to extend implementation deadlines, for instance. How? I would like to find out the answer to that question together with the Platform Economy lectorate of The Hague University of Applied Sciences and the parties involved.