How and why does the platform worker protest? Scientists provide overview and insights.

Do you want to know where, when and how platform workers protest? The Leeds Index of Platform Labour Protest provides answers. In The Gig Work Podcast, Martijn Arets asks the initiators of this project for their key insights for science and practice.

Taxi and delivery platforms determine the working conditions, access to labour and pay of millions of workers worldwide. This frequently leads to protests by this group of workers. Reporting on such protests is mostly incomplete: news reports deal with isolated incidents and often give little background information. This is undesirable, because understanding the dynamics behind these protests, the wishes of workers and the organisation of protests are essential to finding solutions.

That is why a research team from the University of Leeds (UK) has mapped nearly 2,000 worker protests. This Leeds Index of Platform Labour Protest shows differences and similarities, for example between the platform economy and the regular labour market.

For The Gig Work Podcast from the WageIndicator Foundation, I took the train to Leeds for an interview with Vera Trappmann and Simon Joyce, two researchers behind this project.

Why an index?

Trappmann explains that the multidisciplinary team of the Leeds Index of Platform Labour Protest consisted of a group of six researchers, each with their own fascination with platform work. Besides Joyce and Trappmann, researchers Loulia Bessa, Denis Neumann, Mark Stuart and Charles Umney are also involved in the project. The researchers' common problem was lack of understanding and overview of protests worldwide.

"We knew something about protests with us in the UK, for example, but very little about protests in, say, Italy or Argentina," she explains. "Let alone that we could make comparisons. We wanted to do something about that. Not just for ourselves. The aim was to compile a database that would be useful for everyone involved, from activists to trade unions and policymakers."

Collecting data

A first big challenge was data collection. For this, the researchers worked with GDELT (Global Database of Events, Language, and Tone), a joint project of parties such as Google, Yahoo and several independent programmers. This software searches for data in newspapers worldwide, collects relevant info and translates the texts. In this way, the Leeds Index of Platform Labour Protest gained access to millions of news stories about protests by platform workers.

Through the GDELT database, they can also look up specific information. For example, in which countries are workers demonstrating against Uber? The researchers have mapped motivations, appearances, people involved and duration.

"Machine learning makes data collection easier, but interpretation remains human work," says Trappmann. "We needed a big team for that. To give you an idea: there is now information on more than 2,000 protests in the index. So that was a big job, in which we were fortunately helped by a large group of postdoctoral researchers."

Informal occasional formations

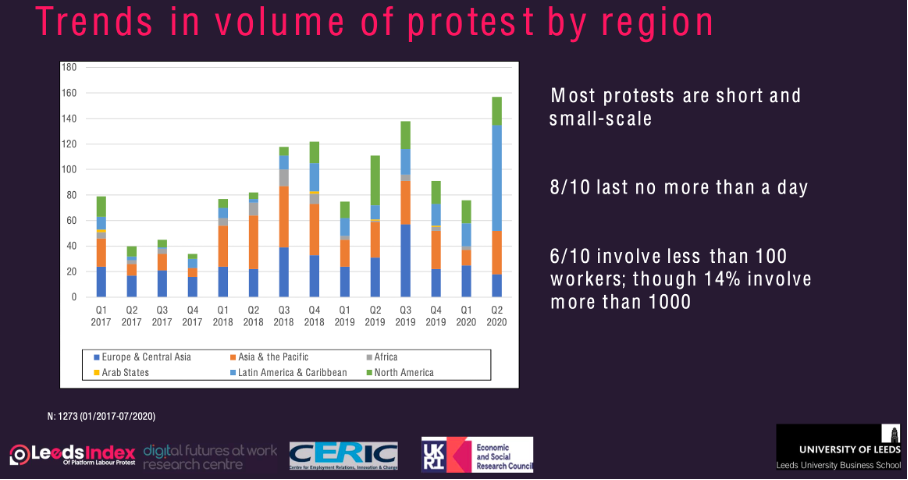

The index has now been around for three years and is providing more and more insight, for example on what makes protests by platform workers different from old-fashioned strikes. The work done by taxi drivers and delivery drivers is not new. Protests in these professions are also not entirely new, but are more common among platform workers.

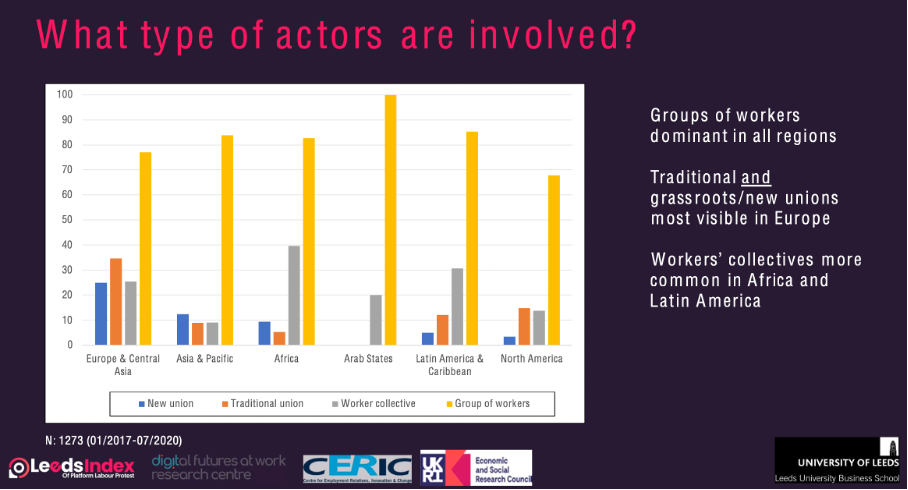

"The big difference is that drivers used to often really work as sole traders or for a small company," Joyce explains. "Now they all work through one big platform. The fact that several workers have complaints about a common opponent leads them to seek each other out more easily to take action. These protest groups are often informal occasional formations, whereas previously they were more often initiated by a union."

Working relationship less important than pay

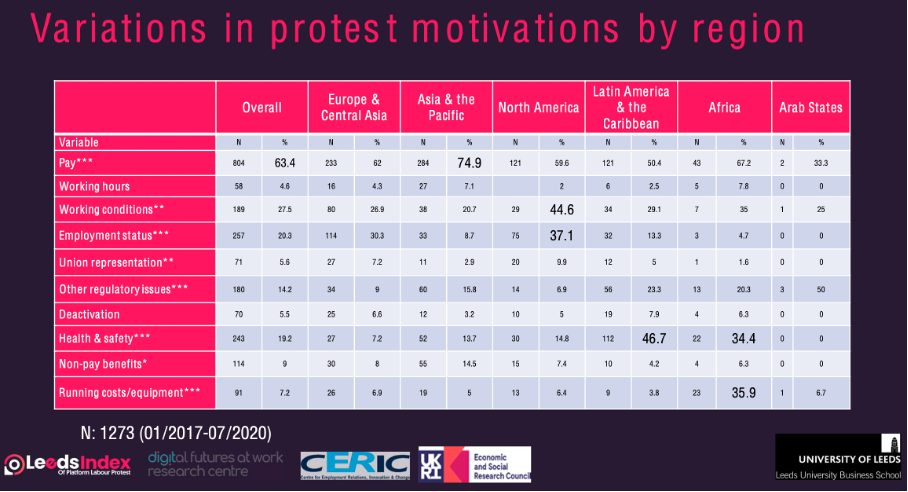

In the US and Europe, there are many debates about the employment relationship of platform workers. In other words, are they employees or self-employed? That issue is far from universal, Leeds Index of Platform Labour Protest data show. Joyce: "So being an employee is not equally valuable everywhere. In Europe, for example, an employment contract means you are entitled to a minimum wage, elsewhere in the world it is not."

The index shows that platform workers worldwide have by far the most complaints about pay. Logical, Joyce thinks. "Platforms lured drivers to their app with the promise of earning more money," he explains. "They deliver on that promise for a while, but soon the algorithm puts pressure on rates. That's a big problem, especially for platform workers who depend entirely on work through the app."

Joyce also frequently spots trends that he can trace back to other developments. "For example, we saw that platform workers in South America were more concerned about health and safety issues during the corona pandemic," says the researcher. "I am sure that in another five years we will be able to analyse much more information."

On location platform work

Currently, the information is specifically about protests by on location platform workers, such as taxi drivers and delivery drivers. Joyce: "Although online platform workers also unite and protest, their protests are much less visible."

Eventually, the researchers want to extend the data to more occupational groups. "We can also apply our research method to protests that are not about the platform economy," says Trappmann. "For example, we are already working with the International Labour Organisation to map protests in the healthcare sector using our methodology."

Furthermore, they have started a series of country-specific reporting of protests by platform workers. The researchers are also open to collaborations, for example with unions that want a report with information on a specific sector.

Trade union more often involved

Indeed, although most protests by platform workers are organised informally, the trade union is increasingly playing a role. "Our analysis shows that in 30% of cases worldwide a trade union is involved," says Trappmann. "In half of the cases the initiative comes from that union, the other half of the time such a union later joins the group."

Trappmann thinks this is positive. She sees all kinds of ways in which existing unions can support the new protest groups. To do that, though, they need to listen carefully to the wants, needs and ideas of those workers.

Tips for the union

"Old-fashioned strikes may work for workers, but they don't suit platform workers," she explains. "My tip to unions: be open to new ideas and real cooperation with these informal groups. Delve into their needs, learn from them and support where you can."

When platform workers organise, these collaborations are often short-lived. How can a trade union movement perpetuate its relationship with platform workers? "I know of examples of unions that have hired platform workers and that works well," she says. "That way, they secure knowledge and keep a connection with the target group."

Conclusion

It is clear that the team behind the index is doing important work. It is incredibly valuable for all kinds of stakeholders that there is now more insight into the organisation and goals of protests and international differences. For me, the Leeds Index is a good example of how researchers can make not only scientific but also social impact.

What strikes me most is that the motivations of workers vary greatly from continent to continent. Platform workers in Asia are above average more likely to fight for higher pay (74.9%). In North America, they stand up for their status and working conditions, while in Latin America and Africa it is more often about health and safety. Platform workers in Africa also regularly protest for compensation for the materials needed to carry out the work.

Such data and insights give better insight into the forms of protest and the wishes of workers. The team behind Index is objective and also looks at the context of the various platforms. This is particularly pleasing. I will definitely accept the invitation to visit again in five years' time; I am eager to see the developments and lessons learned.